Thomas Haigh

Inventing Information Systems

The Systems Men and the Computer, 1950 1968

Business History Review Vol 75, No. 1 (special issue on Computers and Communication Networks), Spring 2001, pp. 15-61.

During the 1960s, many academics, consultants, computer vendors, and journalists promoted the "totally integrated management information system" (MIS) as the destiny of corporate computing and of management itself. This concept evolved out of the frustrated hopes of 1950s corporate "systems men" (represented by the Systems and Procedures Association) to establish themselves as powerful "generalist" staff experts in administrative techniques. By redefining the computer as a managerial "information system," rather than a simple technical extension of punch-card "data processing," the systems men sought to establish jurisdiction over corporate computing and to replace accountants as the primary agents of managerial control. The apparently unlimited power of the computer supported a new conception of information, defined as the exclusive domain of the systems men (assisted by operations research specialists and computer technicians). While MIS proved impossible to construct during the 1960s, both its dream of all-encompassing automated information systems and the resulting association of information with the computer endured into the twenty-first century.

During the late 1950s and early

1960s, a new and exciting concept swept through corporate

Many of the largest American firms began to use computers to automate their most routine administrative processes during the late 1950s. A decade later, the systems men s labors had dramatically changed accepted wisdom on the correct use of computers. In the process, the systems and procedures department was essentially merged with the computer department, and the corporate systems analyst became a computer specialist. The computer s proper role had been transformed, rhetorically at least, from a simple clerk-replacing processor of data into a mighty information system sitting at the very heart of management, serving executives with vital intelligence about every aspect of their firm s past, present, and future. Its contribution could be evaluated not in terms of administrative cost savings but through improved performance of the entire business. And, far from coincidentally, the creators of such systems would have to work closely with executives, assert broad authority over management of the firm s operations, and assemble battalions of analysts, programmers, modelers, and other experts under their command.[2]

The systems men were but one of many groupings of technical staff experts that proliferated within American business corporations following the Second World War. In order to legitimate their authority, these experts had to assert centralized corporate control over activities previously performed by divisional line managers. Like scientists and engineers, the systems men claimed to possess a body of objective knowledge and techniques qualifying them to make superior decisions within a particular technical domain. But their task of legitimation was uniquely difficult because their claimed domain was management itself. To succeed, they had to shift the barriers between the technical and the managerial erected during the early twentieth century to protect and demarcate managerial authority from that of engineers. The authority of the engineer had been confined to a technical sphere he or she might one-day advance to executive status, but only by shedding one identity and assuming another.[3]

The beauty of MIS was that it tied together a whole set of operations that managers already thought were important (such as reporting systems, financial controls, and production scheduling) and bound them to the exciting but disruptive technology of the computer, thus blurring distinctions between the technical and the managerial. It achieved several goals at once. First, by identifying the computer as a tool for the construction of management information systems, it established the jurisdiction of the systems men over the burgeoning world of corporate computing. Second, the new emphasis on the provision of information and control to top management furthered the managers long-standing quest for recognition by executives as more than just clerical specialists and narrow technicians. Third, the new analytical category of management information lumped together certain domains that the systems men had previously been reasonably successful in asserting control over (such as forms, office machines, and clerical procedures) with a host of others that they aspired to control (such as management reports, organizational restructuring, and strategic planning). Systems men hoped that acceptance of the MIS concept would help them transform their success with the more mundane aspects of information systems into a much broader mandate to act as what a few pioneering authors called information engineers. [4]

For about a decade, from its introduction in 1959 to the end of the 1960s, this very broad definition of MIS spread rapidly and was endorsed by industrial corporations, consultants, academic researchers, management writers, and computer manufacturers. Only during this era and in this context was the now commonplace concept of information as a distinct, abstract, yet universal and impersonal, quantity first established in business culture. But the totally integrated information systems originally envisioned proved impossible to construct, leading to some public retreats toward the end of the 1960s. In the 1970s, MIS was redefined in many different ways by these various constituencies, each reflecting a part of the original vision. Grand definitions were gradually given up in the face of experience, and though the term became if anything more common during the 1980s, it shed these now embarrassing associations with the youthful optimism of corporate computing. Despite this, the vision of the computer and information systems as central to a new approach to management has endured to the present. So has the close linkage of information with the computer, the identification of the computer expert as an information specialist, and the paradoxical situation that information is at once the mundane stuff processed in massive volumes by computers, a readily available commodity that permeates the Internet, and the vital resource that powers managerial decision making and corporate success.

Introducing the Systems Men

Economic mobilization during the Second World War brought an

incredible increase in industrial output and placed a premium on the integrated

planning of production and distribution. Work simplification plans, printed

forms, organizational charts, process charts, and instruction manuals were

produced for use on an unprecedented scale. This wartime experience impressed

many administrators with what could be accomplished when organizational

structures and procedures were carefully crafted to achieve specific ends,

rather than accreting slowly over time. In 1944, a number of these administrators

met in

Their systems movement took place largely within the society of corporate management. It was concerned above all with the establishment of the systems and procedures department as a respected, autonomous, and well-funded staff group that could sweep away antiquated methods and spread efficient practices throughout the firm. The papers presented at their International Systems meetings, which were published in the magazine Systems & Procedures Quarterly, exhibit a fixation on questions of status and power: what the group should be named; to whom its leaders should report; how large should it be; what work should it undertake; and how top management could be convinced of its utility. Following the war, American business experienced a sustained and rapid boom. As companies merged, diversified, and set up international subsidiaries, the multidivisional decentralized structure, once confined to a handful of giant enterprises, became the dominant corporate model. Growth, reorganization, and the separation of divisional line operations from corporate staff activities provided a nurturing environment for the new function to take hold.

The association s leadership was dominated by heads of the systems and procedures departments of large and very large industrial firms. For example, in 1950 its two vice presidents worked for General Foods and Montgomery, Ward & Company. Its president, Raymond Cream, was from the ill-fated Baldwin Locomotive Works. Consulting and professional services firms were, however, never without some representation. Cresap, McCormick & Padget (a leading management consulting firm) supplied a director, and Price Waterhouse donated the services of an assistant editor to its journal. Other officers in this era came from the oil, finance, and insurance industries.

The career of John Haslett, manager of methods and procedures for the Shell Oil Company, was a model for his contemporaries. Haslett was a prominent systems man for more than two decades. He helped to found the SPA, was the first editor of its journal, and served for a time as vice president. Haslett went to Shell in 1947, after working in the Army during the war to set up shipping controls and procedures. At Shell he pulled together initially uncoordinated approaches to handling office procedures, reports management, and office equipment to establish broad authority over administrative methods. The result was that clerical work became more centralized and relied increasingly on specialized and automated machinery, such as punch-card systems. Haslett was a frequent speaker and writer on systems management, generalizing his own experiences into a professional agenda. Many of Haslett s pronouncements were concerned with the inevitable evolution of the systems man and the systems and procedures department, from narrow methods specialist to systems-oriented analyst.[5]

The terms, systems, procedures, and methods covered similar ground. In the early days of the SPA, methods was the term most firmly established in corporate use: the methods analyst might be known less formally as a methods man and might work in a methods department. But, to the systems men, methods was a restrictive term, which suggested too intense a focus on detailed execution and insufficient attention to broader managerial issues. Systems implied a much broader mandate. As Haslett wrote in 1950, The systems man can no longer be solely methods minded. He must be management minded. The term systems analyst was used as a more formal variant as early as 1951, although it did not gain wide acceptance except among systems men involved in work with computers. Although many SPA members worked in departments with names like Organization and Methods, Business Procedures, or Administrative Services, they all considered themselves and their colleagues systems men, and, in their view, the name Systems and Procedures Department would most accurately reflect their function.[6]

The language of systems was not, of course, a new one for business. The tools of systematic management (forms, charts, files, reports, written procedures) had been crucial to the emergence of large-scale corporations during the late nineteenth century and to the creation of a professional identity for the career manager. Indeed, the leading general business magazine of the early twentieth century was System. The main distinction between earlier systematic managers and the corporate systems men who made up the bulk of SPA s rank-and-file membership lay in their position within the corporation. To quote the association s treasurer, There is nothing new about systems and procedures; the only new thing is the staff activity concept. The systems men were staff experts and internal consultants though, in practice, most worked somewhere in the depths of the accounting department. They tried to separate technical expertise in the efficient use of administrative techniques from the executive role that had formerly accompanied this mastery. In this they were inspired by the high profile of the technocratic systems approach in Cold War science and engineering.[7]

The systems men also sought to distance themselves from two

groups that had previously failed in similar attempts. One comprised

efficiency experts. On several occasions, Haslett conjured up the Tayloresque

specter of the now abhorrent efficiency expert who lopped off clerical heads

to the cadence of a stopwatch and whose poisoned legacy still blighted the

reputation of

As one might expect from their choice of epithet, the systems men were, almost without exception, male. During the 1950s, masculine pronouns were still assumed to encompass both sexes, and man was widely used make general pronouncements about the human species. But the systems men seemed to have another motive as well: their universal adoption of the term during the early 1950s to define their community (after previous occasional uses of methods man or systems people ) perhaps reflected an attempt to build a specifically masculine identity, and in particular to separate themselves from the appreciable number of women working in the lower-status job of office manager.[9]

Although most SPA members worked in corporate staff positions, consultants and business-school professors played an important role in setting its agenda. They spoke frequently at the association s meetings and shared both its concern with improved administrative techniques and its promotion of a strong systems and procedures department as the vehicle for spreading these techniques. Many of the most vocal figures of the systems movement moved back and forth between corporate positions, academic jobs, and private consulting practice. I use the term corporate systems men here to refer to those employed within corporate staff departments, and the more general term systems men to also include academics, consultants, and business-equipment suppliers who were members of the SPA or frequent guests at its events. Even Haslett himself became a consultant in the end, after two decades with Shell. Successful systems men seem to have gained access to consulting positions far more readily than to top management, despite their frequent assertion that systems work should be the best grounding for future executives.

Indeed, the intellectual manifesto of the systems movement was provided by McKinsey & Company consultant Richard F. Neuschel. In his book Streamlining Business Procedures, published written in 1950, he wrote persuasively of the importance of better administration to organizational effectiveness. Neuschel s recipe for a procedures research department made interdepartmental coordination its crucial goal, rather than the worthy, yet narrow, improvements in clerical efficiency he associated with specialist office management. The true pay dirt in procedures research came only when the systems man reported directly to the chief executive and addressed vital structural matters, such as the relationship between jobs and organizational units and structural barriers to overall profitability. Neuschel firmly subjugated his analysis of specific tools and work aids, such as surveys, flow charts, and tabulating machines, to this higher end. He wanted to turn a collection of specialized techniques into a much broader kind of explicitly managerial expertise. McKinsey was, after all, in the business of management consulting. An open-ended procedures program carried out directly for the chief executive in order to improve corporate coordination would fit much better with McKinsey s carefully cultivated image than would a less exalted focus on technical efficiency.[10]

Neuschel s ideas spread among the more ambitious of the

corporate systems men as well as the rapidly expanding body of management

consultants. The systems men loved to paint themselves as guardians of the

overall corporate interest in contrast to the selfish parochialism of

departments. SPA president F. Walton Wanner (of Standard Oil,

During the 1950s, the SPA boomed as thousands of firms

initiated or expanded their efforts in this area. By the end of the decade, the

systems men had found a niche in the institutional form of the corporation. But

this tenable gain granted them neither the authority nor the security to which

many aspired. When defining the natural duties of their profession, its

members followed Neuschel and emphasized glamorous activities, such as

operations research and what they called the management audit : a staff probe

of how a department controls, plans, sets policies, and utilizes its personnel

and management capabilities. Their core activities, however, remained more

mundane. Profile of a Systems Man, a 1959 survey by the SPA of its

members in 1,100 companies, found that their daily work remained within the bounds

of activities first espoused by office management reformers early in the

century. While around 80 percent of these systems groups were entrusted by

their firms with procedures manuals, forms control, and clerical work

simplification, only a small proportion claimed to practice operations research

or to perform management audits. Less than one-third supervised five or more

people. Most systems men were college educated (primarily accounting and

business degrees) and in their thirties or forties. The bulk of them worked for

manufacturing firms in the Northeast or

The systems men s most fundamental weakness was the fuzziness of all-round expertise in management methods as a claim to professional expertise. Indeed, they complained that systems departments were liable to be the first to be cut when a company fell on hard times. As the systems men frequently lamented, it was very hard to turn recognition as an expert on forms into a mandate to reorganize processes across departmental boundaries. A 1959 warning given by a leading British practitioner captured their dilemma:

[H]e claims to be an expert in a subject which most other business people claim to be equally expert. What does the system man know that the office manager, or indeed, any other manager does not know? . . . There are already growing up in the office field a number of other techniques which do not suffer from these disadvantages. There is the computer programmer who has learned a secret language. There is the operations research man who, as a mathematician, employs unassailable mathematical techniques. . . . Each has his esoteric techniques to sell. But what has the systems man which is not the everyday currency of everyone else in business?[13]

The Systems Men and the Computer

As this warning suggests, the computer loomed above the systems men of the late 1950s, offering what seemed an unparalleled opportunity to overcome their managerial marginality. In that same 1958 speech in which he placed systems work at the heart of management itself, Wanner had also argued that the computer opens doors heretofore not open to systems activities. Acknowledging that top management had previously been at best half-hearted in its attention to paper-handling techniques, he optimistically suggested that the appeal of the computer had changed this refractory attitude. The new electronic tools allowed the systems man to cross departmental lines at will, merging and consolidating work on a truly functional basis, eliminating unnecessary departments, and re-engineering and replanning the entire system. [14]

Unfortunately for Wanner and his colleagues, the jurisdiction of corporate systems men over the computer was unclear during the 1950s. After IBM coined the term electronic data processing (EDP) to describe the function of its administrative-oriented computers, punch-card supervisors adopted data processing as an umbrella description of the work of computer, punch-card, and paper-tape machines. IBM stood to gain if computers were seen as a natural extension of the existing punch- card operations that still accounted for the bulk of its revenues, and so did the punch-card managers. Existing investments in mechanical punch-card equipment provided both technological and human continuity between computers and mechanical tabulating machines continuing a process of evolution that was already decades old. As a result, when the computer arrived, it was often the punch-card staff who became its stewards. To mark this transition, in 1962 the punch-card machine supervisors association changed its name to the Data Processing Management Association (the DPMA). According to its executive director, Calvin Elliot, the association was no longer merely an organization of Tab Supervisors. Elliot claimed that A new professional data processor [is] being created, with a combination of line and staff responsibilities requiring strong technical know-how as well as managerial abilities. This threatened to usurp the territory of the systems men themselves.[15]

Despite its attractions, involvement in data processing threatened two key goals of the systems men. The first, shaped by the failure of the office managers to overcome their role as head clerks, was to avoid at all costs becoming direct supervisors of clerical production. They wanted to define new systems as consulting staff experts, not oversee their daily operation as plodding office supervisors. The second was to remain management experts rather than technicians specialized in one or two tools. Is the analyst turning into an artisan making application of punched card and magnetic tape equipment? asked one of their kind. An analyst for Air Canada lamented that a misled faith in the computer cure all was sometimes abetted by mesmerized systems and procedures personnel who were so engrossed in working out the complexities of machine procedures that they unconsciously became completely computer-oriented and convinced that machine handling was the only way. [16]

Systems men frequently tried to paint EDP as a mere technical specialty within their broader domain, alongside better-established specialties such as records management, form design, or work measurement. They made similar claims regarding operations research, a widely publicized but relatively rare staff activity that enlisted natural scientists to investigate ways to apply their mathematical techniques to problems of corporate administration. Operations research pioneers insisted that their scientific approach was the first rigorous and logical assault on the most crucial problems of business, denigrating the corporate systems men and relying on the cultural authority of science to trump their own lack of practical business experience. This was another threat to the claims of the systems men to be the only group of generalist experts in efficient management methods. Systems men therefore painted the specific tools developed by operations researchers (such as queuing theory, decision theory, and linear programming) as a useful but narrow specialization within the overall systems department.

The challenge to the leaders of the SPA was to assert control over the computer without seeing its membership trade their managerial dreams for careers as programmers. Those working intimately with computers found themselves immersed in a new world, which demanded the acquisition of specialized, craft-based technical skills. The most powerful computers of the 1950s could hold only a tiny amount of information in their high-speed internal memory (the equivalent of today s RAM chips). This memory had room for a simple program, some totals and counts, and the single record currently being processed. Early computers worked like machines on an assembly line repeating the same operations as records were passed through them one at a time. Each application, such as payroll, was split into a number (perhaps ten or twenty) of runs. A typical run took the intermediate-results tape of a previous operation and cycled through it, performing a simple task, such as the deduction of union dues from the already calculated weekly pay packet. Achieving these tasks with any level of efficiency required the same concern with physical flow as the establishment of an efficient manufacturing plant. Programmers interacted directly with the physical hardware of the computer: loading numbers into specific memory locations, specifying exactly what operations to perform, and grappling with the enormously complex steps required to read information reliably from tape drives and send it to printers. Each program was so laboriously tailored to its task that modifying its function even slightly could prove a major undertaking. A fundamental redesign might be needed in order to take advantage of a memory upgrade or the installation of additional tape units.[17]

During the late 1950s, an increasingly wide cultural gulf separated computer programmers and analysts from their former comrades in accounting, office management, and systems and procedures. Scarcity of experienced computer staff raised their pay scale and made it easier for them to move between than within companies, ensuring that data-processing staff bonded more closely with each other than with their nontechnical colleagues. Many systems men had a particularly low opinion of the new breed of computer specialists without experience in broader administrative work. One such analyst slammed the specialists who had buffaloed management [but whose] bubble was now bursting. While such technicians had perhaps, a real talent for working with numbers, they could not compare to the true systems man who remained a professional advocate of the management techniques. Of course, he also had little time for former systems men [who] have joined the ranks of EDP or computer technicians and abandoned the systems profession. Neuschel himself was quoted by Fortune in 1957 as saying that electronic equipment was rarely needed and that he had not yet recommended EDP to a single client. The proliferation of computers intensified the dilemma: whether to embrace data processing or stick with the broader, yet problematic, mandate of the administrative systems expert. The computer had the attention of top management, a distinct glamour, and a degree of tangibility and security that more traditional systems could never match. On the other hand, to cast one s lot with the data processors was to give up the aspiration of becoming a true management specialist.[18]

Information and Management

The systems men dealt with this quandary by redefining the computer as a managerial tool for the creation of systems to deliver information to executives rather than as a technical device for the processing of data. They would become specialists in information systems a concept invented during the 1950s and popularized during the early 1960s. Within a decade, they had succeeded in asserting their own control over corporate computing and in gaining wide (if still theoretical) acceptance of the computer as a tool for management improvement rather than clerical automation. Discussion of information is so ubiquitous today that it is hard to recognize the novelty and power the idea held during the 1950s, or to read historical uses of the term without interpreting them in the light of modern definitions. Philip Agre has written: Information is not a natural category whose history we can extrapolate. Instead, information is an object of certain professional ideologies, most particularly librarianship and computing, and cannot be understood except through the practices within which it is constructed by the members of those professions in their work. [19]

To understand the appeal of information to the systems men

and the ways in which they shaped subsequent understanding of the concept, we

must first explore what information meant within managerial culture during the

1950s. Contemporary commentators were well aware that there was little

discussion of information in the abstract. Dun s Review pointed out to

the world of industrial management in 1958: [O]nly in the past dozen years has

the concept of information as distinct from the papers, forms, and reports that

convey it really penetrated management s consciousness. That it has done so is

largely due to recent breakthroughs in cybernetics, information theory,

operations research, and the electronic computer. . . . Others concurred

as to the novelty of information and its intimate association with the

computer. One management professor claimed: As late as 1946 there were in the

combined professional, technical and scientific press of the

Of course, neither the word information nor most of the things to which it was applied were new. As one might expect, information was originally the event that took place when a person was informed of something. According to linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, during the late nineteenth century, use of the word shifted to refer primarily to structured, objective, and systematically disseminated forms of communication, such as newspapers and reference works while retaining an earlier association with personal improvement. In the early twentieth century, the term information was frequently associated with communication (especially in the public relations sense), with intelligence (in the military sense), and with the acquisition of knowledge. It continued to imply that a human recipient was being informed (just as the word education today implies that a person is being educated). Think, for example, of an informant, a well-informed reader, a memo stamped For Your Information, or a public information bureau. Information was a quality possessed by something that informed, or a process by which one became informed, but not a commodity in its own right.[21]

Information gained a new cachet from information theory, a

scientific approach codified by communications engineer Claude Shannon in 1948

(based on a usage of information in communications engineering and statistics

that preceded his achievement by several decades).

The issues addressed by information theory were fundamental

to the design of computers that could store data and move it between different

internal components for processing. This relation between computer and

information was the organizing theme of Edward Berkley s seminal 1949 book, Giant

Brains, or Machines That Think the first to introduce electronic computers

and their potential use in business to a general audience.

The inherent efficiency of automation was a given. Widespread coverage in the business and popular press exaggerated both the prevalence and complexity of automated production lines. When enthusiasts of the 1950s promised that electronics would revolutionize society they spoke of automation, not of information. Although Peter Drucker explicitly discussed automation in his seminal 1954 book, The Practice of Management, he also briefly touched on information as the tool of the manager, defining it as a manager s ability to communicate his ideas to other people through the use of words and numbers. At this point, neither the association of information with the computer nor the idea of the information system had gained general managerial recognition.[25]

Office automation consultant Howard S. Levin was among the first to turn information into a claim to organizational power. In 1956 he argued, in Office Work and Automation, that to view office work as equivalent to business information handling requires [that] we consider. . . the executive who analyzes budget requests as well as clerks themselves. Levin made many claims for information: it was the basis of all decision making; investment in information was vital to future prosperity; information handling was synonymous with office work; information costs would be sharply reduced by the computer. He argued for business to support a new breed of information specialists or information engineers and a vice president information to improve its effectiveness. Information was a single word that could mean many things: it encompassed clerical work and strategic decision-making when both were abstracted as different kinds of information processing. Levin achieved this by eliding differences between the new, technical sense of information as a quality processed by a clerk or a computer and the older sense of information as the knowledge obtained from various sources that allows management to make informed decisions. This association of information with the computer, and specifically with the use of the computer in business, preceded more general theories of the information revolution or information society. Only in the late 1950s did Drucker coin the phrase knowledge worker to describe the increasing importance of technical and managerial workers. The extension of this idea by others to the more general and more technologically focused information society did not take place until much later.[26]

Levin was also one of the very first, at least in a business context, to draw a distinction between information and data. During the 1950s, the two were usually used interchangeably in discussions of management or computing a pattern Levin followed in most of his book. At one point, however, he suggested that data be viewed as the raw factual material stored in computers or copied by clerks. Information, in contrast, was useful knowledge data that had been manipulated so as to inform the recipient about the state of business. From the late 1950s, the term information was increasingly claimed by groups wishing to be seen as managerially oriented and was invoked in opposition to the humdrum masses of data processed by machine-minded computer and punch-card technicians. The distinction is still widely made today, although subsequent rhetorical devaluation of information has led to the addition of knowledge, and even wisdom, to this hierarchy.[27]

In 1958, two University of Chicago Business School professors, Harold J. Leavitt and Thomas L. Whisler, put together computers, information, automation, and management and redesignated the computer as information technology. Their Harvard Business Review article, Management in the 1980s, depicted a future in which this combination of computer hardware, operations research methods, and simulation programs had transformed the corporation. The computer remained a tool of automation, but it had spread its reach beyond the manual labor of clerks to transform the work of management itself. Middle managers had largely disappeared after computers automated their decision-making duties and removed their autonomy. Leavitt and Whisler likened the new organizational shape to a football balanced on a pyramid. Executive ranks had been swelled by researchers, or people like researchers, who had stronger technical skills and demonstrated a rational concern with solving difficult problems. Management would spend most of its time tweaking decision-making systems, rather than making individual decisions. In staff roles, close to the top were to be found the programmers of management science, free to perform their own research and decide what and how to program. Decentralization and delegation, two crucial developments of the 1950s, had merely been unfortunate necessities that were fortunately no longer necessary.[28]

The ideas of Leavitt and Whisler stimulated a great deal of activity

within management research, and some of their specific predictions were

challenged especially their idea that computer technology dictated managerial

centralization. In addition, the phrase information technology did not enter

general usage until the 1980s in the

The appeal of this science-fiction future to operations research and management science researchers is quite obvious. But it also stirred a flurry of interest among corporate systems men, for whom the association of the computer with information and executive management provided a welcome alternative to the identification of computers as data processors. For Leavitt and Whisler, previously differentiated items, such as accounts, market forecasts, and inventory records, were now grouped under a single heading (information) and demarcated as the professional responsibility of a single group (the information technologists). Leavitt and Whisler concluded their article with an appeal for executives to search for lost information technologists languishing unappreciated within the staff ranks. The systems men wasted little time in volunteering themselves.

The New Vision: A Totally Integrated Management Information System

Instead of borrowing Leavitt and Whisler s term, information technology, systems men created another phrase that fused information more directly to their existing claims to expertise in overall systems rather than narrow technologies: the management information system (MIS). In 1959, Charles Stein, a senior member of the consulting firm United Research, defined this integrated management information system as a computerized tool that would meet all the information needs of all levels of management in a timely, accurate and useful manner. Variations on this phrase were to appear hundreds of times over the next decade. The management information system was singular for a firm: it described one system that tied together all others. More than this, it would include mathematical models that would instantly feed back information on the impact of any decision on corporate-level goals. Every departmental decision could be evaluated instantly and empirically for its impact on corporate profits, thus banishing forever the problems of organizational politics. Facts would speak for themselves.[30]

Stein s definition, and indeed the phrase management information system itself, made its public debut in 1959 at a small conference, under the title Changing Dimensions in Office Management, which was sponsored by the American Management Association (AMA). Speakers at the conference included representatives of computer manufacturers, academics, consultants, heads of professional associations, and prominent corporate systems men. This was the first presentation of the results of a working group, called the Continuing Seminar on Management Information Systems. The group was convened by Gabriel N. Stillian, a fellow of the IBM Systems Research Institute and head of the AMA s Administrative Services Division. It also included Stein, senior representatives of McKinsey, and top systems men from industrial giants such as Lockheed and DuPont. These corporate participants emphasized the need for such a project to be headed by a strong manager who would be able to cut across departmental boundaries and would adopt a systems-oriented, rather than a machine-oriented, viewpoint. Conference speakers from Univac, Honeywell, and RCA were keen to promote the potential of their machines as management tools, predicting the imminent emergence of a top-level staff manager to organize every level and every kind of information in the company via control of electronic and manual data processing, corporate planning, and operations research activities. The term MIS made its first appearance during that year, in a U.S. Navy report on the use of computers to construct a single integrated system to manage all Navy resources.[31]

MIS was in many ways an extension of integrated data processing (IDP), one of the largest-scale and most technologically advanced systems and procedures activities of the mid-1950s. Integrated here suggested that data should be transferred directly from one office machine to another, using punch cards or paper tape rather than being retyped many times. New kinds of teletype machines and automatic typewriters even allowed transmission of orders directly from head office to remote warehouses. This promised accuracy, speed, and efficiency. Although this concept predated widespread use of the computer, its appeal was only strengthened as computerization proceeded. MIS was IDP writ large, emphasizing better decision making rather than operational efficiency and applying techniques from operations research to transform mere data into managerially relevant information. MIS united this idea of integrated automatic systems with the reports control, another popular idea among the systems men, whereby a systems group would take control of all the reports prepared for different levels of management, consolidate redundant information, eliminate reports that were no longer needed, and judge the economic merits of each request for a new report before approving it. Unlike the conceptually similar activity of forms control, reports control was rare in practice, probably because it required the systems men to challenge the rights of line managers to control their own reports.[32]

The MIS idea spread rapidly throughout the administrative systems community, encouraged by a spate of subsequent reports and conferences sponsored by the American Management Association. In 1961, the association published the first book-length treatment of MIS, Management Information Systems and the Computer, authored by James A. Gallagher, a recent McKinsey hire and member of the continuing seminar. Gallagher had previously worked in data-processing management at Sylvania Electric Products and in the systems planning department of Lockheed Aircraft. In MIS, contrary to the ideas of Leavitt and Whisler or Herbert Simon, the computer would not automate management decision making, but it would automate the supply of information to management, and so raise the status of systems work while linking systems work and data processing as two parts of the same whole. According to Gallagher, a total management information system controlling the entire business automatically is not in the foreseeable future, but a system which will keep all the firm s management completely informed of all developments is perfectly possible of achievement. As this choice of words shows, MIS was an information system because it informed managers, not because it was full of information in Shannon s technical sense, though the distinction soon blurred as the idea of MIS spread.[33]

The same year, the conference program of the SPA was suddenly awash with papers on the total systems concept. Haslett, for example, claimed that Shell was on the threshold of a totally integrated management information system. Throughout the early 1960s, the systems men used terms such as management information system, totally integrated management information system, management systems, information systems, MIS, total MIS, total systems concept, totally integrated data processing system, totally integrated system, and total system interchangeably and ubiquitously. The latter was the vaguest and initially the most popular; for the sake of coherence, MIS is used here to refer to all of them. Exactly what made a system total was never quite agreed upon. An early book devoted to the subject introduced the total system as a totally automated, fully responsive, truly all-encompassing information system embodying the collection, storage and processing of data and the reporting of significant information on an as-needed basis. Despite the obvious problems inherent in building such a system, similar definitions were widely propagated throughout the 1960s.[34]

As Roger Christian, who presented the SPA s introductory conference seminar on the topic, admitted, Most definitions seem to carry elements of a job description. The power of the phrase rested primarily in its opposition to the unsatisfactory and limited nature of existing arrangements. It enshrined the mandate, long sought by systems men, to cross organizational boundaries. Christian used the new idea of information systems ( To be effective, information systems must be designed engineered if you prefer ) to justify elevation of systems men over both accountants ( There is a distinct cultural lag among accountants; fortunately it s time industry took control of information systems out of their hands ) and data-processing technicians ( Armed with high-speed hardware and a crusader s zeal, these people can literally clog the organization with paper, meaning that managers aren t getting information at all they re getting reams of data ).[35]

Although total systems (like systems analyst ) was a term

borrowed from cold war systems engineering, corporate systems men gave the term

their own meanings. They looked up to the systems engineers and operations

researchers of RAND, but their community was largely separate from this

cold-war elite, and even from industrial engineers working within their own

companies. As the total systems concept spread, the exact meaning and degree of

its totality were earnestly discussed. Most definitions insisted that the label

applied to the whole of the firm s operations, although opinions differed as to

whether this implied that everything had to be computerized. Even the limits of

the corporation itself were insufficiently total for some, who suggested

( [O]

On system in particular, SABRE, was aggressively promoted as proof of the applicability of real-time operation and the systems approach to corporate computing. Developed at huge cost by IBM and American Airlines, SABRE allowed travel agents to use specially designed consoles to interrogate a central computer directly in order to view flight availability and make reservations. Even before its completion, Gallagher used SABRE as a case study of MIS technologies in his 1961 book, and it has been a textbook example of the strategic use of computers ever since. As the first such system used for business purposes, SABRE was widely reported and served as an apparent demonstration of the desirability of real-time access to business data. Its success was used to justify investment in unproven, indeed as yet undeveloped, technology. Gallagher noted: [F]rom the beginning, they planned a system based on future technology requirements. They did not wait for the new technology to develop. . . . SABRE also provided management information as a byproduct of handling routine transactions, leading some to claim it as a management information system. Of course, reservation clerks had a more tangible need for instantly (as opposed to weekly or monthly) updated status information than did senior managers, but most discussion of on-line, real-time systems in the mid-1960s ignored this fact entirely.[37]

During the early 1960s, all these ideas fused as they spread from the elites of the AMA group through the rank and file of the systems and data-processing communities. The manifest destiny of both corporate computing and corporate systems work became a real-time, on-line, totally integrated management information system that delivered all relevant information to all managers in a timely, complete, and accurate manner. Managers would make better decisions more rapidly, assisted by complex models and simulations built into the system. In conjunction, these propositions formed the manifesto for what Dun s Review and Modern Industry called a Managerial Revolution. The systems men were part of a very broad array of fellow travelers working toward this goal. The same period saw a new interest in management theory and self-conscious experimentation with organizational forms. Fashionable techniques included business games, budgeting systems, operations research, and formalized approaches to strategic planning. These approaches fitted together well. For example, in order for a computer to sound the alarm when a performance target is missed or a budget exceeded, a managerial mechanism for setting such targets must be in place. All involved reliance on the computer and a new class of staff experts, supported by a cast of managerial technicians. Like most utopian visions, this one offered its true believers a better, cleaner world that made perfect internal sense: what James C. Scott has called a high modernist ideology of technocratic control.[38]

Selling MIS and the Third Generation

One class of companies stood to benefit most dramatically from this revolution. Computer vendors loved the idea of turning their machines from labor-saving office equipment into the indispensable core of modern management itself. Not only would this give computing a direct and respected job serving the firm s senior decision makers, but it would also involve the purchase of vast amounts of the newest and most expensive computers, terminals, communication equipment, and disk storage units. Because of IBM s stranglehold on traditional data processing, smaller players, such as RCA, GE, and Univac, concentrated on designing and promoting equipment suitable for managerial applications. These firms promoted their computers at essential technology for the creation of MIS.

During the mid-1960s, computer makers cemented their commitment to the new vision of real-time, on-line, managerially oriented systems by promoting their latest computers as part of a new, third generation of computer technology. (The generation concept was widely accepted in computing circles: the first consisted of vacuum tube based machines; the second, of those built from transistors.) These machines were intended to take technologies for operating communications in real time, which had been pioneered in systems like SAGE and SABRE, and integrate them into every data-processing center. A cluster of capabilities built into new hardware and operating systems made it much easier for the user to interact with computers. Video terminals and the ability to run several programs simultaneously allowed system loads to be balanced because the computer could deal with urgent on-line requests while running routine batch jobs with its spare capacity. Much larger internal memories, coupled with high-speed disk storage (the precursor to today s hard-disk drives), made it possible to keep relatively large volumes of information available for immediate retrieval ( on-line storage ). The capabilities of these machines seemed almost limitless. Given the increasingly well-publicized difficulty of saving money by replacing cheap clerical labor with million-dollar computers and expensive programmers and analysts, one of the biggest appeals of MIS to computer salesmen of the early 1960s was that its benefits would emerge in the overall performance of management making them impossible to measure. The author of an MIS textbook quoted with approval the head of MIS for General Electric as arguing, If an MIS can be justified on the basis of cost savings, it isn t an MIS. [39]

The computer salesman s most potent weapon was the growing constituency of computer-dependent staff within their customer organizations. These people had tied their lives to computer technology and generally identified more strongly with their occupations and skills than with their firms. Systems men saw a way of claiming control over the burgeoning field of corporate computing while strengthening their claims to general managerial authority. Computer specialists hoped to shed their reputation as introverted technicians and obtain a more prominent, respected organizational role. Operations research practitioners were keen to move beyond specialist service groups to build their models directly into the management systems of the company itself, with the result that, by the 1970s, MIS had subsumed previously separate operations research groups in many firms. MIS and the new third-generation computers promised all these groups a kind of class mobility within corporate society, and they seized it enthusiastically.[40]

The systems men attempted to sell management information to corporate-level executives as a tool for the control of far-flung divisions. Without leaving their desks, they could know more about the operations of their unruly divisional subordinates than those people knew themselves. This vision cast the systems men themselves as the indispensable servants of corporate control. Their aspiration was to become a powerful managerial group rather than a lowly service organization. No longer would they be called in to write reports that nobody read or to fight fires and fix pressing, but trivial, problems that operating managers could not be bothered to fix themselves. Addressing the problems of the firm s total information system meant reorganizing departments, merging redundant operations, and slashing inefficiency and waste wherever they found it. They offered an implicit bargain to corporate executives: You put us in charge and we ll deliver to you more power over your firms than you ve ever dreamed of. [41]

This rosy vision was inevitably contrasted with a dismal view of the present and accompanied by dire warnings about the failure to act, ranging from individual bankruptcy to the threat of revived foreign competition to enslavement as a result of losing an economic war with the frighteningly efficient Soviets and their advanced planning and modeling techniques. Thus, almost every article written or paper delivered during the 1960s on the topic of general business experience with computers began with a denunciation of the widespread failure to realize anticipated economic benefits through simple clerical automation. Many of them cited a landmark 1963 McKinsey study, published in the Harvard Business Review, which found that two-thirds of large companies were failing to achieve savings. The authors insisted that the reasons for this were managerial, not technical. Among the study s recommendations were extensive top-management involvement, the aggressive application of computers to managerial, rather than clerical, matters, and the imposition of proper managerial discipline on the data-processing operation itself. These findings were repeated and eventually were transformed into a kind of folk wisdom, which held that real payoffs would emerge from computerization of reporting and other systems that crossed divisional lines.[42]

Other authors used similar condemnation of the status quo to further their own professional agendas. They seldom blamed machines themselves, or programming difficulties. Instead, they invoked the idea of an inherent true potential of computers, which was unfortunately being squandered through mismanagement of one kind or another. This idea became such a clich that it led to publication of a whole genre of articles, all opening with a brief allusion to the well-known failure of computing to fulfill its potential before moving rapidly to justify a particular set of remedial measures. All the authors sounding this theme agreed that the situation was a dismal one but had different ideas for a cure. Depending on their point of view, they might advocate better communication, more attention to industrial psychology, packaged software, structured programming, or improved training for analysts. Each prescriptions could usually be traced to a writer s own area of professional expertise. However, by presenting their ideas as a set of reforms that were essential for unleashing the value locked inside an expensive and uncooperative computer, these different experts tried to turn their own attempts to ascend to corporate power into matters of urgent necessity.

Like the traditional systems and procedures departments and punch-card departments, the computer departments of the 1960s were usually under the authority of the controller or another financial executive. While converts to the computer saw its potential for application to tasks within and across various operating divisions, they complained that their accountant superiors were conservative, distracted by other matters, and possessive of the prestige attached to the new machine and the prestige it conferred. Of course, others could deploy the same evidence and rhetoric of failure to draw the opposite conclusion. L. C. Guest, GTE s controller, defined failure in much the same way, but attributed it to a lack of discipline and financial controls by a new class of management seeking total control over data processing. Soon, when the controller reasserted his rightful authority, the word intangible would be stricken from the vocabulary of all data-processing and systems groups and the computer s true potential would appear.[43]

The Information Pyramid: A Challenge to the Controller

By staking a claim to information as a general and flexible method of corporation-wide control, MIS made a direct challenge to the controller and his corporate accounting staff, whose ascent to corporate power was built on their ability to turn operating figures into financial reporting and control data. This attack on accounting was propelled in large part by the desire of the systems men to emancipate newly combined systems and computer operations from the control of financial managers. Many presentations at systems and data-processing conferences featured organizational charts, with which the converted preached to each other the gospel regarding their departments right to report directly to the corporate president or chairman rather than to the controller. During the 1950s, this was a suggestion that was offered tentatively, and as a topic for debate, but it soon became an article of faith among the systems men if not among executives.[44]

As Alfred Chandler and contemporary theorists were then elucidating, a multidivisional firm could only hope to perform better than its more specialized competitors when it rested on its ability to coordinate operations and allocate resources more efficiently than classical market mechanisms allowed. Enthusiasts promised to use MIS to give managers of the biggest and most sprawling conglomerate an overview of the firm. Savvy consultants were careful to make their pitch seem less threatening by pointing out that information was already the lifeblood of business and thus that every firm, by definition, already had a management information system. The problem, they said, was that the current ad hoc one was no good. For example, Charles W. Neuendorf (a consultant, former Air Force colonel with responsibility for management information systems, and chair of the Burroughs Systems Advisory Board) argued that the total management information system was merely a tool used with facility by our forefathers during the era of small businesses, but pushed aside and all but forgotten with the advent of big business. The idea that MIS could make any global business as easily manageable as a family store had particular appeal during the 1960s when firms such as Litton Industries and Textron were relying on the allegedly universal merits of good management and superior systems to justify expansion into wholly unrelated areas of business.[45]

Systems men seeking autonomy from the controller thus tried to turn the tables on accountants by arguing that it was traditional financial control, rather than computerized management, which was hopelessly technical, out of touch with the real world, and fundamentally unmanagerial. They insisted that the worst thing about current information systems was their domination by accountants. MIS and accounting systems were both intended to take details of the smallest individual transactions (a single line on an invoice) and from these create a hierarchy of reports, summaries, and totals. The systems men had little respect for the formalized and slowly developing practices of accountancy. They felt that accounting was only one major subsystem of the overall management information system and that they were best placed to design the overall system. They criticized accountancy for being backward looking delivering information on the past performance of a business rather than on its current state or (via models and simulations) its future. They criticized it for being inflexible and ritualistic more concerned with the observance of due process than the usefulness of its output. The challenge of MIS to accountants dominant role as suppliers of control systems to management therefore hinged on its ability to do a better job by overcoming their alleged pedantry and historical fixation. As a result, a great amount of rhetoric was devoted to its ability to forecast conditions and to highlight and interpret the important pieces of information in a sea of routine data (often called the management by exception principle).[46]

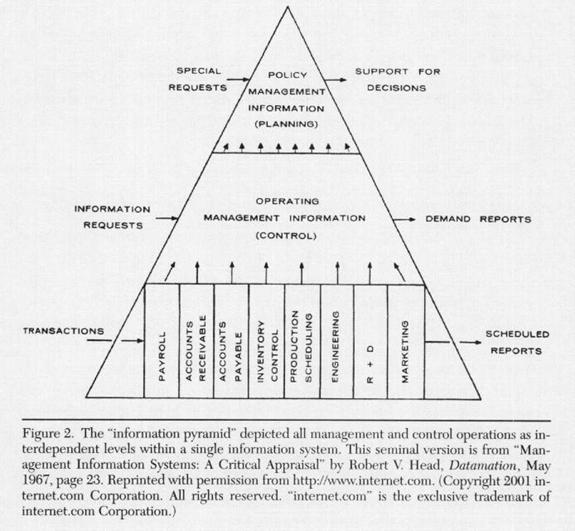

Corporate managers had long understood their firms as pyramids defined by supervisory relationships, where authority passed downward from a narrow apex to a broad base. The systems men borrowed this metaphor to describe another pyramid what Paul R. Sanders, who was then leading American Airlines attempt to turn SABRE into an all encompassing MIS called the Information Pyramid. Drawings of such pyramids eventually became a standard part of definitions of MIS. MIS was the whole of the pyramid the skeleton of a new pyramid of automated information systems that would entirely subsume existing accounting and control functions. This pyramid had as its bottom level the mass of routine, operation systems, such as payroll and invoicing, that formed the mainstays of existing computer use. Information entered the pyramid at its base and was distilled and processed as it moved upward. In the middle level sat routine reporting and analysis for day-to-day control. But it was the topmost levels that seemed to support claims of a managerial revolution: here, middle-management decisions were automated, x models of the firm s overall profitability were constantly updated, and interactive facilities allowed executives to manipulate data and ask what if? questions. Into these topmost levels would be fed sales targets, economic information, and other managerially relevant information.[47]

Only the new, broad, and mechanistic understanding of information and the constantly evolving blue sky technology of computing made this pyramid credible. Redesignating everything from payroll slips to strategic planning as part of a huge, interconnected realm of information gave credence to the systems men s insistence that all processes formed a single system that must be planned and controlled as a whole. High-status strategic-planning information, they insisted, could only be produced as a byproduct of low-status, routine data processing. As information experts, the systems men would control this new system, and so assert their domination over more narrow specialists, such as EDP staff, operations research analysts, and accountants. Like so many other expert groups, they were involved in making claims about the inherent nature of things; by doing so, they were establishing a perceived world in which the value of their expertise was self-evident Acceptance of information and systems techniques as a kind of universal expertise would give the systems men enormous managerial power.

The systems men s claims to a generalized authority based on

information acumen did not go unchallenged. Their most vociferous critic was

John Dearden, an expert on financial controls at the

Dearden s most fundamental challenge to MIS was his insistence that no generalized set of principles or practices linked different kinds of management information. Dearden observed that the systems men had achieved some success in tackling the problems many corporations were experiencing in logistics by tying together production, distribution, and ordering procedures. This area had been an organizational vacuum in many firms, and he was willing to concede that it deserved to be one of a small number of firmwide vertical information systems, joining better-established systems for accounting and personnel. But he ridiculed the idea that such techniques could be applied to the provision of information and control systems in areas like finance or marketing, whose information needs were entirely separate. The systems approach, he added, is merely an elaborate phrase for good management. If companies were having problems with their financial-control systems, then the answer was to recruit better managers. The only advantage that computerization could possibly offer would be lower administrative costs.[49]

Dearden questioned the very idea of a systems profession, decrying a tendency to classify certain people as information systems specialists and certain organization components as systems departments and then to consider these people and departments as specialists in the entire continuum of the development of an information system. The technical work of programming, rather than the managerial work of system specification, could be given to a centralized staff group. During the mid-1960s Dearden was one of only a few critics to dispute publicly the wisdom of the systems men s dreams; many may have shared his views but expressed them through ignoring the topic. To the boosters of MIS he seemed like a lone reactionary who failed to understand what they were saying. But as time went by and the promised breakthroughs failed to arrive, the tide began to turn.[50]

MIS: Some Dreams Have Turned to Nightmares

The biggest problem with MIS turned out to be the impossibility of building one. MIS was, to borrow a term from the 1980s, perhaps the ultimate in vaporware: an exciting technology that never quite coalesced. There is no record that any major company managed to produce a fully integrated, firmwide MIS during the 1960s or even the 1970s still less one that included elaborate economic forecasts or linked suppliers and producers. While technical and managerial communities were flooded with materials describing the idea of such systems, practical guides explaining how to get to there from here were conspicuous by their absence. Those that did appear, in places like the low-circulation Total Systems Newsletter, offered platitudes on the need to carefully plan and manage the product and to diagram and test the code. Careful study of task diagrams with boxes that might be labeled finish the design did little to bridge the enormous technological and organizational barriers standing between dream and reality.[51]

During the mid-1960s, many companies published eager boasts about ambitious MIS projects under development, putting pressure on their competitors to announce similar programs. These firms included Pillsbury, General Electric, Proctor and Gamble, Weyerhaeuser, American Airlines, Lockheed, and Litton Industries. RCA offered for emulation a plan for MIS based on rigorous analysis of its entire business that would take ten years to go from initiation to completion. Only a few firms, mostly those (like IBM, RCA and Univac) with computers to sell, claimed to describe fully operational systems. Even these articles followed a pattern of starting with a description of lofty plans for real-time operation and integration before outlining the a reality that was far less exotic. For example, RCA applied the MIS tag to a spare-parts inventory system that periodically issued accounting reports for management. Because a management information system was eventually supposed to include everything, pretty much any system could be called phase I of the much larger effort. This thinking was surely encouraged by the fact that information for different jobs was stored on the same computer: how difficult could it be to patch them together? But, as actual experiences mounted, problems came into sharp relief.[52]

One problem was the difficulty in discovering what information managers actually needed. The original assumption had been that one could move down the company ladder, beginning with the president, asking each manager in turn what information he needed to do his job. Then one could design a system to deliver the right information, carefully tailored for each person s requirements. Unfortunately, managers turned out to be rather poor at articulating in formal and complete terms exactly what they needed to know. And, even by the most optimistic time scale, the effort would take years to deliver a system, which by that point would surely be out of date. Likewise, the programs themselves created a spiderweb of interdependencies. Because they shared files and fed information back and forth, the slightest change to the data format used by one could incapacitate all related operations, which, according to the total systems ideas bundled into MIS, meant every aspect of the company. Business information requirements changed constantly. The software tools, operating systems, and project methodologies developed at this point could not begin to tackle the job.

Computer hardware of the era, though powerful enough to inspire enormous confidence when compared to earlier machines, was hopelessly inadequate to the task of building a MIS. Systems men and management consultants tended to state as a matter of faith that business results achieved with computer hardware were constrained much more by poor management and unimaginative application than by technological limitations. While largely true, it did not follow that the computer hardware of the 1960s was powerful enough to support any conceivable system still less that this could be achieved economically.

MIS was ubiquitous in theory and unknown in practice. A 1966 survey of manufacturing firms conducted by the consulting firm Booz, Allen and Hamilton found that firms were beginning to follow expert advice by using their computers for more than just routine administrative tasks and then auditing the effectiveness of the results. But, although every single one of the thirty-three firms surveyed was reported to be working on objectives for an ultimate total systems concept, not one took seriously the idea that of connecting the inputs and outputs of their computer programs as an immediate goal, not did any firm plan to install a terminal in its board room. Two years later, Richard G. Canning, publisher of the thoughtful and respected newsletter EDP Analyzer, asked, What s the Status in MIS? He concluded that the best currently deployed systems were limited, but useful, producing scheduled reports of genuine value to top management but making little use of management science techniques. Little real interest existed among top management for graphical displays or personal interaction with the system. However, he expected increased use of mathematical models and the incorporation of information from outside the firm during the years to come.[53]

By 1968 a backlash against MIS was taking shape within elite corporate management, which was chronicled by Fortune, Harvard Business Review, and McKinsey. Tom Alexander of Fortune claimed that although business was computerizing faster than ever, managers found their investments ever less productive as they moved further from clerical automation: Most companies even the most advanced seem to agree that computers have been oversold or at least overbought. It turns out that computers have rarely reduced the cost of operations, even in routine clerical work. He suggested that managers were losing faith in the ability of models and simulations to automate their work or to transform decision-making into an exact science.[54]

Meanwhile, accountants struck back. An author from Arthur Young and Company, for example, warned of looming danger in MIS driven by na ve managers and unscrupulous consultants. Accountants had been warning for some time of the dangers of computeritis, eager computer salesmen, and a romantic attachment to totality. Sensitive to such criticism, the elite consulting firms pulled back from grand claims and reasserted their managerial credentials. A much-quoted McKinsey report of 1968 dismissed, almost in passing, the so-called total management information systems that have beguiled some computer theorists in recent years and challenged the very idea that executives were ever going to use computer terminals directly. The report concluded that top management must take control of computing itself; it could not abdicate control to staff specialists, however gifted as technicians. The next year, in a piece entitled MIS: Some Dreams Have Turned To Nightmares, a McKinsey consultant, Ridley Rhind, endorsed Dearden s view of computerized MIS as a useful but limited tool, best suited to operational management and logistics. [T]he data that are collected to assist in the management of daily operations are basically of very little interest, even in summary form, to the top management of the corporation. Rhind went on to dismiss the dreamlike quality of most articles on total systems: [P]romises that the computer can eliminate shortages, delays or inaccuracies in available information are made only by those who have a vested interest in computer development work and who believe that the more ambitious the system, the greater the status. Expertise in computer systems, he insisted, did not translate to expertise in management control systems.[55]

Even management science researchers with an interest in modeling techniques began to retreat from the idea that a group of staff experts should produce an enormous model of the whole company to be used by the president in evaluating major decisions. Curtis H. Jones, another Harvard expert, suggested that such models gave only an illusion of optimality while freezing and hiding assumptions made by the model builders. Models should support management decision-making, not automate it. Rejecting the systems men s idea of MIS as a tool to filter the information given to each manager, he argued, Staff personnel . . . should be charged with the responsibility of expanding, not reducing, the number and range of alternatives which the executives can evaluate easily. [56]

Companies tended to add voluminous statistical output capabilities to their existing operational systems and call the result MIS. They hoped to connect the pieces with analysis and modeling tools at a later date. William M. Zani, a Harvard business professor and computer management expert, attributed this failure to top management s inability to figure out what strategic information was needed and then to assign a suitably powerful systems team to deliver it. Instead, existing systems were automated and recycled, resulting in a management information system [that] is merely a mechanism for cluttering managers desks with costly, voluminous, and probably irrelevant printouts. He concluded, No tool has ever aroused so much hope at its creation as MIS, and no tool has proved so disappointing in use. [57]

The Fate of MIS

MIS did not suddenly go away in 1968. It remained the central topic in discussions of corporate computing well into the 1970s. But its meaning gradually became more problematic and its usage more fragmented over the decade that followed. Indeed, MIS retained sufficient cachet among the elites of the corporate and business-school computing world that in 1968 they chose to name a new, more exclusive, professional association the Society for Management Information Systems (SMIS). Despite this title, members of the new society were never able to agree on what a management information system was. The enduring power of the term derived in part from its very vagueness. A savvy veteran recalled:

[The MIS concept was spread through] a struggle that went on in most companies for control of the whole process of developing systems and operating them. The question was whether such systems were to be operated by broad gauge men or narrow specialists. I think it is useful for us to recall the origin of the term and to realize that it began as a merchandizing gimmick and has been perpetuated to emphasize . . . the types of people who should control the design of such systems.

It was possible to repudiate any popular definition of MIS (perhaps one that stressed totality or seemed too fixated on executive use of terminals) without having to renounce a shared commitment to MIS, whatever it turned out to be. This interpretative flexibility, more than anything else, accounts for the endurance of MIS as a term, even though its meaning was never settled and was always changing.[58]

One of the most important of these diverging approaches to MIS, and one promoted by SMIS founder and SABRE veteran Robert V. Head, emphasized the data base. Rather than constructing a total system in which all management tasks, information requirements, and responsibilities were rigidly encoded, MIS came to be seen as a reservoir for the storage of information shared between all programs. One author called it the collection of all data that are relevant to executive decision making. Managers were expected to decide for themselves which information they needed and to go fishing for it. This reflected an important shift from the original idea of MIS constituting an information system because it was an assemblage of processes acting to inform management, to a more abstract sense of it as being an information system because it stored a lot of information. The system was tended the data base administrator (DBA) originally envisioned as a guardian of all corporate information whose mandate would transcend the technical minutiae of computer systems. Although the practical impact of database systems in the 1970s was as a tool for programmers, the management literature viewed their role as a continuation of the MIS idea. As Richard L. Nolan, author of Managing the Data Resource Function, explained in 1974, Writings on MIS have waned recently and have largely been replaced by writings on the Data Base. [59]

MIS remained a very popular term in academic discussions of corporate computing. During the 1970s, the growing community of university researchers writing in the SMIS journal Management Information Systems Quarterly could reject the approaches to MIS adopted by practitioners while claiming to have devised a new, improved one of their own. Some began to work on constructing more formal methodologies for systems development, while others suggested that an effective MIS could be built only by studying the failure of earlier attempts and discovering how managers actually used information. In business schools, MIS was the main title under which the topic of computers and organizations entered the curriculum. Courses, departments, professors, and textbooks of MIS proliferated in the early 1970s. Many of these textbooks finessed the difficult technical problems and kept alive the dream of a total system. But eventually business schools settled on MIS as a catchall term for the use of computers in corporations. Meanwhile, MIS slowly replaced EDP as the name for corporate computer departments, despite the fact that these departments remained far more involved in routine administrative and operational matters than in managerial decision-making. Information retained its allure, however problematic it proved as a departmental mandate. As Head admitted, It is perhaps the systems designers who really want an MIS, and not the top management group. [60]